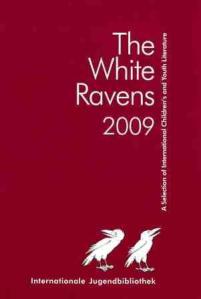

Compared to the Batchelder Awards, which honor between 1 to 4 books yearly, the IBBY Honour List and The White Ravens cover a far greater range of books, countries, languages and literary diversity. The International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY) produces the IBBY Honor List every two years and honors authors, illustrators and translators from its seventy member countries. The 2008 honor list has sixty-nine recognized books, fifty-two illustrators, and forty-eight translators. The White Ravens, awarded annually by the International Youth Library, had two hundred fifty titles in thirty-two languages from forty-eight countries in their 2009 honor list (The White Ravens, 2009). Yet, broad as these award lists are, accessibility of the items can be a very real issue for North American libraries.

Compared to the Batchelder Awards, which honor between 1 to 4 books yearly, the IBBY Honour List and The White Ravens cover a far greater range of books, countries, languages and literary diversity. The International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY) produces the IBBY Honor List every two years and honors authors, illustrators and translators from its seventy member countries. The 2008 honor list has sixty-nine recognized books, fifty-two illustrators, and forty-eight translators. The White Ravens, awarded annually by the International Youth Library, had two hundred fifty titles in thirty-two languages from forty-eight countries in their 2009 honor list (The White Ravens, 2009). Yet, broad as these award lists are, accessibility of the items can be a very real issue for North American libraries.

The International Youth Library (IYL) in Munich, Germany, selects the best and most noteworthy newly published books from around the world each year—designating their picks the ‘The White Ravens.’ They then compile these selections into a ‘White Ravens Catalogue’, which the IYL presents each year at the Bologna Children’s Book Fair in Italy. Unlike IBBY, their selections are not on a strictly one to one basis (i.e. one book from each country) but rather reflect ‘the best’ of the range of books that IYL has received over the year and whether or not they find the selections innovative and worthy of ‘special mention’ or compatible with ‘international understanding’—two special designations that they attach to certain titles (International’s Children’s Digital Library, 2009).*

This year, for example, The White Ravens featured eight selections from Australia—4 young adult titles, 4 children’s selections—which covered a range of topics from self-mutilation to schizophrenia, the Outback to the Easter bunny, and traditional folklore to Arthurian fantasy. Yet, exciting as this range of titles is, the accessibility of titles honored by the White Ravens – even from Australia – is often a problem in North America. Despite there being no translation barriers and widespread availability of many Australian books in Canada and the United States, I was unable to find an easy (and affordable) way to buy or borrow any of these particular titles in North America despite the fact that one of these selections, Finnikin of the Rock, was authored by Melina Marchetta—whose earlier YA novel, Jellicoe Road, won the Printz Award for excellence in young adult literature.

Similarly, I tried to find an easy way to obtain some of the sixty plus books currently honored by IBBY—but to little avail. IBBY does have several excellent resources for collection building available through their organization and website, such as their current virtual exhibit, “Books for Africa, Books from Africa,” (above) that features African books for children and young adults that IBBY has identified and reviewed—along with providing publisher information for the African publishing houses (IBBY, Books for Africa, 2009).

As in the catalogue of the Honor List, IBBY produces a full listing of the contact information for each author, illustrator, translator and publishing house that has been nominated in the list (IBBY Honor List, 2008). Yet, short of placing small book orders from individual publishers, these titles remain wonderful reading suggestions but not necessarily practical solutions for incorporatinging international YA into North America on a large scale. The problem again, as with books in translation, seems to still echo what Gretchen Schwarz said that, “finding [international YA] titles is easier than obtaining books….” (1996).

However, IBBY and the White Ravens do offer a range of titles that surpass the Batchelders not only in number, but also in scope and diversity of topics. The White Ravens have an excellent breadth of titles with some surprising results such as an environmental non-fiction book for young adults, Planeta tierra planeta vida. Pasado, presente y futuro de la vida sobre la tierra (Planet Earth Planet Life. Past, present, and future of life on earth) from Colombia, and a novel about human trafficking and female subordination, Lālāī barāy-i duhtar-i murda (Cradle song for a dead girl), from Iran. The White Ravens are missing selections from countries with large publishing systems like India or South Africa, and there are few selections from Latin America or sub-Saharan Africa; but, overall, the White Ravens do represent a diversity of topics and cultural perspectives.

The IBBY Honor List also offers an expanded worldview of the global publishing industry—offering titles from Bolivia on videogames, virtual reality and dinosaurs [Trapizonda: Un video juego para leer (Trap Zone: a videogame to read)], a Slovenian version of Cinderella (Pepelka), and a South African action adventure in Afrikaans (Thomas @ Aqua.net). However, due to the small number of selections per country, IBBY is not able to offer the same diversity of audience (many IBBY member picks are for very young chidlren only) or topics that the White Ravens provide. But IBBY does provide an exceptionally wide range of selections from a diversity of member countries.

This broad country representation is central to IBBY’s belief, as an organization, of the importance of “provid[ing] insight into the diverse cultural, political and social settings in which children live and grow” (International Children’s Digital Library, 2009). This commitment is underwritten by IBBY’s non-governmental status and official place with UNESCO and UNICEF as a policy-making advocate of children’s books and literary, including its dedication to the International Convention on the Rights of the Child. This political commitment to steadfast representation from its member nations does differ from that of the Batchelder Awards, which are more about competition and regarding certain types of literature than equitable representation. In fact, in 1978 and 1993 no Batchelder Awards were given due to the committee’s operating belief that “in a year that the committee is of the opinion that no book of that year is worthy of the award, none is given” (Batchelder Award, About the Award, 2009).

Overall, selections from the White Ravens and IBBY Honour List may be difficult to obtain, may not be available in English, and, for the IBBY Honour List specifically, may tend to group children and young adult materials together indiscriminately; yet, the scope and breadth of topics in these awards are more reflective of the greater range of opinions and lifestyles of international children. There is war and mass violence impacting many developing nations, but there is also video games and dinosaurs and this diversity should be reflected in any award winning list.

__________________________________________

*books NOT borders note: IBBY will only select one book and one illustrator per member country to honour biennually, though it will honour multiple translators in the case as Spain where it honours both Spanish, Catalan and Basque translators.

___________________________________________

References

Read Full Post »

Named after Africa’s first Nobel Laureate, the

Named after Africa’s first Nobel Laureate, the

The Alex and Michael L. Printz Awards are awarded every year by YALSA to honor noteworthy children’s and young adult literature. The Alex and Printz Awards, however, do not specifically recognize international titles, but global YA titles have often appeared on these award lists – especially in recent years.

The Alex and Michael L. Printz Awards are awarded every year by YALSA to honor noteworthy children’s and young adult literature. The Alex and Printz Awards, however, do not specifically recognize international titles, but global YA titles have often appeared on these award lists – especially in recent years. The

The

The Australian ‘Sisters in Crime’

The Australian ‘Sisters in Crime’  Compared to the Batchelder Awards, which honor between 1 to 4 books yearly, the IBBY Honour List and The White Ravens cover a far greater range of books, countries, languages and literary diversity. The

Compared to the Batchelder Awards, which honor between 1 to 4 books yearly, the IBBY Honour List and The White Ravens cover a far greater range of books, countries, languages and literary diversity. The